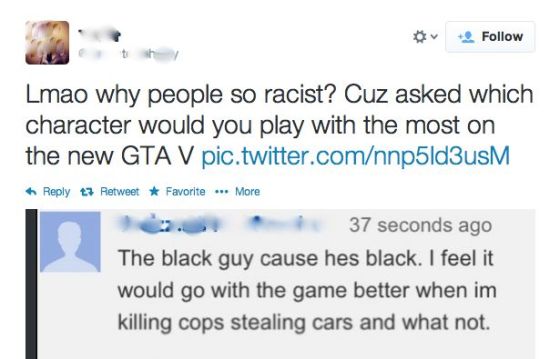

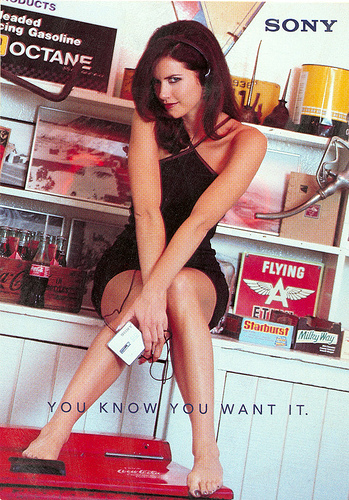

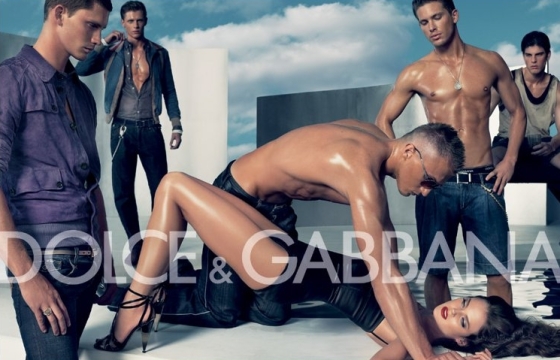

Hip-hop culture originated in the 70s on the streets of New York and south-central Los Angeles, and since has rapidly spread across the globe, expanding from traditional forms. Authentic hip-hop culture was a form of expression, communication and a way to raise awareness of cultural and societal issues. Early genres provided meaningful messages of political consciousness, inclusion, activism, equity, justice, education and success – however commercial hip-hop culture exposes modern manifestations of more negative stereotypes. There is now a stigma associated with hip-hop culture and stereotypes that are predominantly represented in music, gaming and television. The overwhelming repetitiveness of “gangsta-rap” music videos tend to glorify inappropriate behaviour, criminality, brutality, vulgar sexuality and misogyny. Commercial exploitation of hip-hop culture has reshuffled to this commonly presented “gangsta-rap” stereotype, is problematic for youth as they internalise these negative images of racialised ethnicities in the media (Pieters, 2007).

“Music, like identity is both performance and story, describes the social in the individual and the individual in the social. The mind in the body and the body in the mind; Identity, like music, is a matter of both ethics and aesthetics.” (Mitchell, 2007)

Western perceptions of hip-hop are that it is a culture that derived from a genre of music and the derogatory associations the media has portrayed. Hip-hop is in fact a powerful, ancient culture formed by many elements – it is a style, how one dresses, speaks, expresses and carries themselves. Despite all the positive aspects of hip-hop, the media chooses to focus primarily on the negative – seldom exploring the many positive influences that hip-hop culture has brought to the world.

I encourage you to watch (even just 30 seconds) of these two music videos that I feel explore the contrast between traditional and commercial hip-hop culture. As you watch each clip, consider the differences or similarities of elements such as attire, atmosphere, culture/identity, product placement/consumerism, portrayal of men/women/children, instruments, lyrics or any others you can think of.

Pete Rock & C. L. Smooth “They Reminisce Over You”

50 Cent – P.I.M.P. (Snoop Dogg Remix) ft. Snoop Dogg, G-Unit

The first music video provides a more authentic sense of hip-hop culture, yet is not the kind of clip you would see on MTV’s top hits. The second clip, dramatically varies from traditional elements of hip-hop culture, however is extremely similar to mainstream music videos in this genre.

References:

1. Mitchell, T 2007, 2nd Generation Migrant Expression in Australian Hip-hop, Local Noise, viewed 22 May 2014, <http://www.localnoise.net.au/site-directory/papers/2nd-generation-migrant-expression-in-australian-hip-hop/>

2. Pieters, G 2007, Hip Hop Cultures Identity Crisis, The Star, viewed 22 May 2014, <http://www.thestar.com/opinion/article/214702–hip-hop-culture-s-identity-crisis>

Poor Social Media Choices Lead to Lost Jobs and Scholarships, Storify 2014

Poor Social Media Choices Lead to Lost Jobs and Scholarships, Storify 2014