Globalisation involves two processes that have implications for the media; it is the way technologies are able to conquer global distances – creating a world that seems limitless, and the way that a single economic system, ‘the free market’, now permeates the globe.

“Television… now escorts children across the globe even before they have permission to cross the street” (Meyrowitz, 1985 p238)

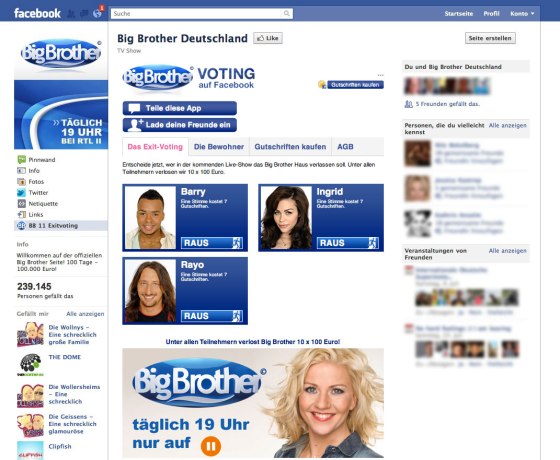

The rise of mass television has allowed millions to regularly observe other people and places, anonymously and from afar – blurring the line between public and private behaviours, and weakening the link between physical location and access to social experience. In this sense, television has contributed to the reshaping of social roles regarding age, gender and authority. Television experience also prompts the prevalent use of participatory media, such as the interaction on social networking sites (Meyrowitz, 2009). A journal article by Jinna Tay and Graeme Turner (2008) investigate how the convergence of media platforms is challenging conventional perceptions of how the mass media function. Television is no longer considered a single entity working in the social, political and cultural aspects of media. New media is recontextualising the way we experience television – since the likes of major rating successes such as Big Brother, which incorporated multi-platformed and multimedia events, it is evident that television is no longer a stand-alone medium.

EG. BigBrother Germany Facebook Voting App – adapting to communication technologies and evolving the TV industry to multiple platforms – leading to new show formats (just as Televoting did in the 90s).

In Australia, television advertising is plummeting as online advertising booms. As a result, market-specific variations are increasing. Television in the 21st century has had to adapt to a demanding, competitive and technologically convergent environment by targeting consumer groups. Broadcasters utilise reality television programs, as they are suitable for cross-media interactivity – taking advantage of modern communication technologies, in turn allowing industries to experiment with younger demographics. This reformation of television challenges authoritarian-style governments across the globe, as they struggle to maintain control, as there is no longer a single foundation to provide a basis for national conversation (Tay & Turner, 2008).

References:

1. Metzger, MCM 2011, Endemol’s BigBrother launches voting via Facebook Credits, Monty’s Blog, weblog post, 6 july, viewed 16 May 2014,<http://blog.monty.de/2011/07/endemols-bigbrother-launches-voting-via-facebook-credits/>

2. Meyrowitz, J 2009, We Liked to Watch: Television as Progenitor of the Surveillance Society, Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 625, pp. 32-48.

3. Meyrowitz, J 1985, No sense of place: the impact of electronic media on social behaviour, Oxford University Press, New York

4. Tay, J & Turner, G 2008, What is Television: Comparing Media Systems in the Post-broadcast Era, Media International Australia, no. 126, pp71-81